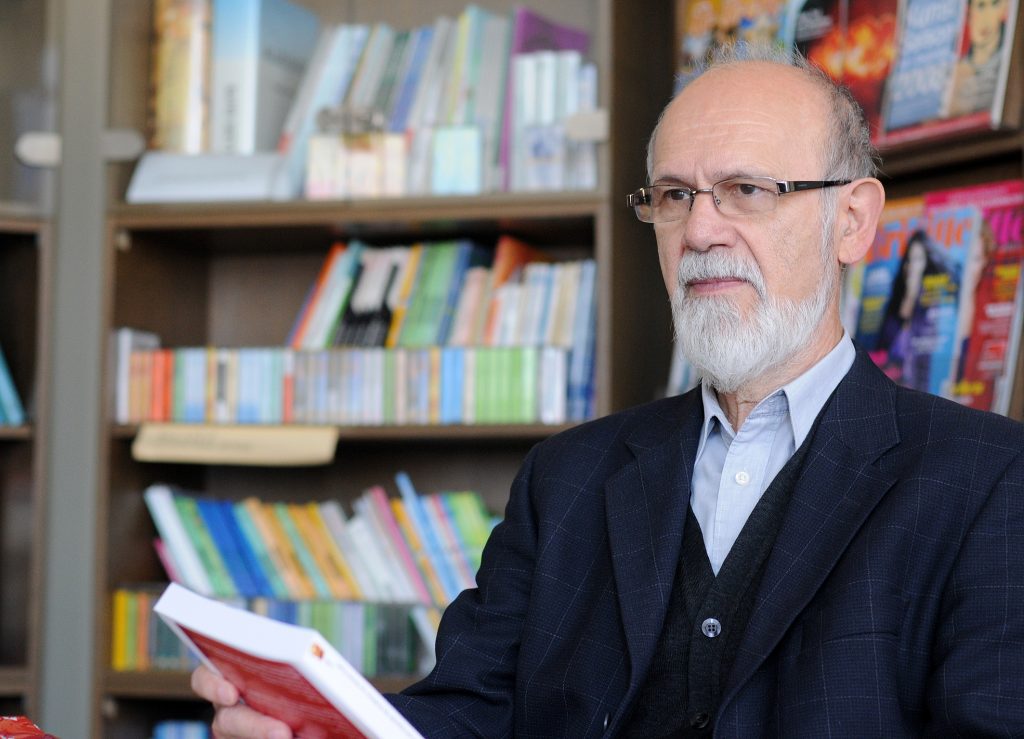

Ranko Risojević (1943), a poet, prose writer, dramatist, essayist, historian of mathematics, translator and cultural worker, has published more than fifty books, including 18 collections of poems, 26 prose books, among which 11 novels, and has had two of his radio dramas for children performed and two dramas for adults staged at the National Theatre of Bosnian Krajina in Banja Luka. He has prepared several books of poetry and prose by our authors for print. He has received numerous awards for his literary work some of which are: the Sisak Ironworks award for the poetry book Prah, Laza Kostić Award for the prose book Šum (Noise), Politikin Zabavnik Award and the award of the “RS Association of Writers, Banja Luka Branch” in 2000 for the novel for the young Ivanovo otvaranje (Ivan’s Opening), the awards The Seal of the Town of Sremski Karlovci and Skender Kulenović for the poetry book Prvi svijet (), the award The Poet – A Witness of the Time of the Sarajevo Poetry Days in 2000 for Samoća, Molitve (); Branko Ćopić award of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts for the novel Bosanski dželat (The Bosnian Executioner), Kočić award for entire opus, Dušan Vasiljev award in 2010 for the novel Gospodska ulica (The Gentlemen’s Street), and from the Association of Writers of RS, Branch of Banja Luka the Gračanica Charter for the entire literary opus. In addition to translations from his lyrical and prose opus, the novel Bosanski dželat (The Bosnian Executioner) has been translated into Russian, German, Polish and Czech, the novel Šum() in Italian, the children’s novel Dječaci sa Une (Boys from the Una) in Macedonian. Boys from the Una are on the mandatory reading list for schools in both B&H entities.

He is a Knight of the French Order of the Academic Palms.

Prose books: Umjetnost Marije Teofilove (The Art of Marija Teofilova, stories, 1974), Nasljedna bolest (Hereditary Disease, novel, 1976), Slike za utjehu (Pictures for Consolation, poetic prose, 1981), Veliki matematičari (Great Mathematicians, biographical stories, 1981, three editions), Priče iz novena (Newspaper Stories, 1982), Dječaci sa Une (Boys from the Una River, children’s novel, 1983), Tijelo i ostalo (The Body and the Rest, novel, 1987), Priče velikog ljeta (Stories of the Great Summer, stories for the young, 1988), Slavni arapski matematičari (The Famous Arab Mathematicians, stories about Arab mathematicians, 1988), Trojica iz Zrikovije (Three Guys from Zrikovija, children’s novel, 1990), Sabalasni šinjel (The Spooky Greatcoat, novel, 1993), Šum (Noise, short prose, 1995), Ivanovo otvaranje (Ivan’s Opening, novel for the young, 2000, 2001), Vlado S. Milošević – jedan vijek (Vlado S. Milošević – an Era, biography, 2001), Fragmenti (Fragments, short prose texts, 2002), Bosanski dželat (The Bosnian Executioner, novel, 2004, 2005), Arheolog (The Archaeologist, novel, 2005), Simana (novel, 2007), Duhovni tragovi (Spiritual Traces, essays, 2008), Gospodska ulica (The Gentlemen’s Street, novel, 2010), San i java i drugi postupci, Dreams and Reality and Other Procedures, stories, 2013), Minima memorabilia (short story sellection, 2014), Noć na Uni (A Night at the Una River, novel, 2014), Sestre i drugarice (Sisters and Girl Friends, novel, 2016) and Beskućnik (A Homeless, novel, 2017).

FROM REVIEWS

The new novel by Ranko Risojević A Night at the Una River does not leave indifferent anyone who has suffered traumas of war destructions and whose intimate living space has been cut in half with an imposed, hermetically sealed border.

Shaping and combining (…) two stories, after about a dozen novels of unequal reach, and after twice as many poetry collections, Ranko Risojević has written another suggestive and powerful book, which, like his Bosnian Executioner, is a page-turner. We owe this extraordinary satisfaction to the magmatic density of his evocative narration on the one hand, and the rare fire of his narrative imagination on the other; highly-acclaimed dynamics, rhythm and storytelling, on both.

Marko Paovica about A Night at the Una River

The Gentlemen’s Street might be seen as a catalogue of names, with the note that the title has its German form – Herrengasse. This leads us to Bosnia, to Banja Luka, at the time of the Austro-Hungarian administration, at the pre-war, war and post-war time. And thus all the conditions are there, given in this convergence, for the writer of experience and gift to successfully continue his trilogy, this time in the second sequel. I say all the conditions, because there is no time more favourable than a hard one (which means: for people unfavourable in every sense, deadly) to stir up a novel, seasoning it with passions, virtues and vices, the good and evil, love and going to war, man after man.

Miro Vuksanović about The Gentlemen’s Street

Neither traditional, hyper-modern nor seductively postmodern, Risojević is a writer of depth, of symbiosis of poetic openness and dark rhetoric, but also of a discursive and rational firmness, confidence in knowledge and its sobering power to break down the mythological and romantic prejudices of literature and its escapist fervours. His prose is an expression of maturity and an endeavour to confront a real human world cloaked in fiction, with narrative powers to evoke a certain kind of thinking about the dark modes of the world in which we live by distinctive gestures.

Jovan Zivlak about The Gentlemen’s Street

The fact that he brought into close relationship an Orthodox priest’s family and a family of a qadi, perhaps today – after the interreligious and interethnic conflict in Bosnia at the end of the last century – seems unusual, even slightly idyllic in its civility and openness towards “others”. By depicting these earlier, suppressed examples of a civilized, tolerant and confidential life of members of different religions, the writer has offered an appropriate critique of the interreligious and interethnic conflicts of our time, a critique of intolerance and hatred that is now found in many people from mixed as well as “ethnically cleansed” communities.

Stevan Tontić about Sisters and Girl Friends

On the whole, in the novel Simana, Ranko Risojević depicts with great talent and through interesting individual dramas of human life, landscapes of Banja Luka’s history in the period when the Austro-Hungarians were establishing their authority. These landscapes are often recalled with memories of previous times, with the hints of what was to come, and especially of what the creation of the Serbian trading class in Banja Luka would bring; a class that changes relations in the city life, often in conflict with religious leaders. His story partly unfolds in the fruitful tradition of Andrić’s narration where the elements of realism float in the same space with human dreams and hallucinations, but also in a particular technique of evoking different voices that interpret or question what is happening in the fictional fabric of the novel.

Svetozar Koljević about Simana

While the emphasis in The Gentlemen’s Street was on the fact that, although the narrator is a book character, he gets as much information as possible about everything and everyone (through letters, diaries, etc.), in A Homeless Person the focus is on keeping everything else closed so that the reader’s attention is directed at the windows of the building of Djordje’s mental house, its contents, the layout of rooms and furniture in them. Within this inner world of his, the reader is drawn into the situation to truly observe the city, characters and events through the eyes of the narrator, who, although internal, the reader believes.

Sanja Macura about A Homeless Person