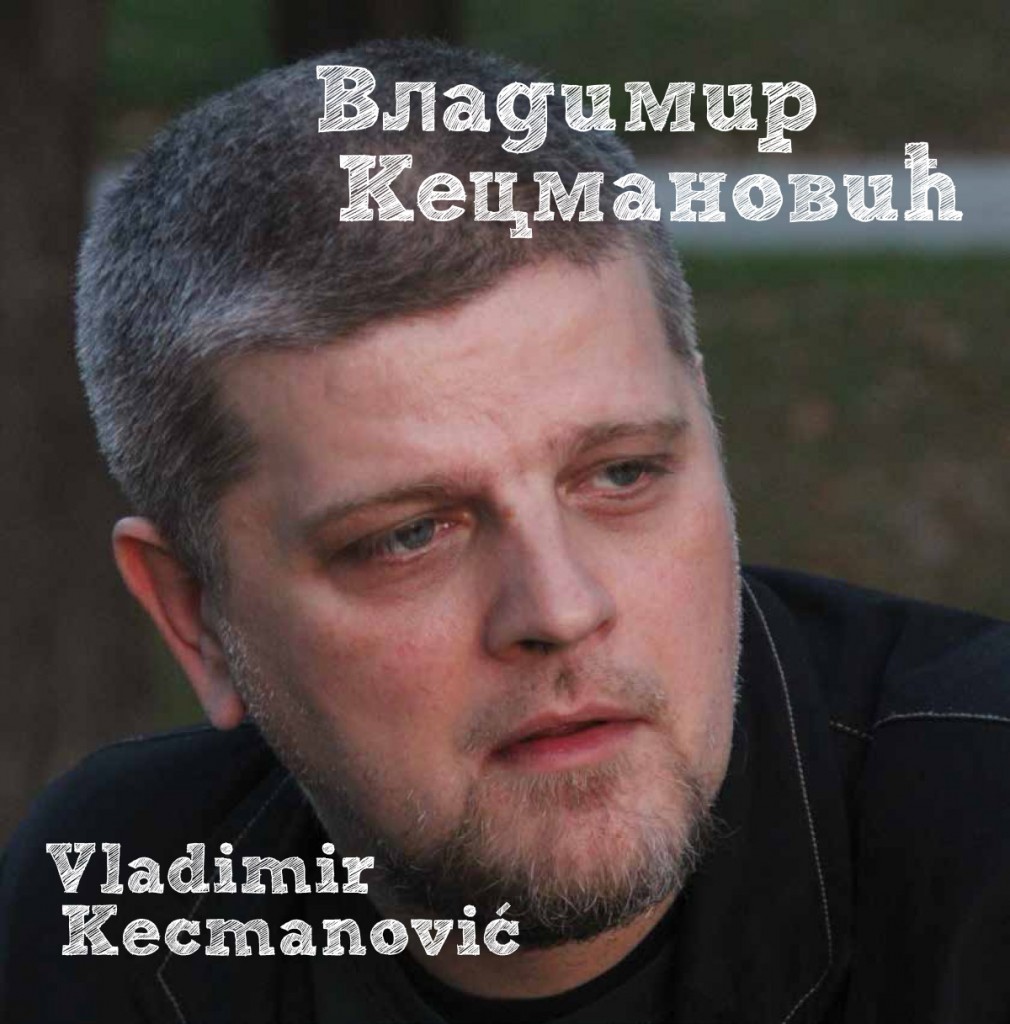

Vladimir Kecmanović (Sarajevo, 1972) has published the novels: Poslednja šansa (The Last Chance, 1999), Sadržaj šupljine (The Substance of a Hollow, 2001), Feliks (Felix, 2007), Top je bio vreo (The Cannon Was Red Hot, 2008), Sibir (Siberia, 2011), Kainov ožiljak (Kain’s Scar, co-authored with Dejan Stojiljković, 2014), Osama (Isolation, 2015) and the story collection Zidovi koji se ruše (The Falling Walls, 2012). He has co-authored the book Tito, Pogovor (Tito, Afterword 2012) with historian Predrag Marković. He has also published an essayistic-biographical book Das ist Princip! (2014).

He has received a scholarship from the “Borislav Pekić” Foundation and awards “Ivo Andrić,” “Branko Ćopić,”“Meša Selimović,” and the great “Andrić Award” of the Institute in Andrićgrad.

Kecmanović’ prose has been translated into English, French, German, Ukrainian and Romanian.

His works have been made into films, and adapted for television and theatre.

The translation of the novel Top je bio vreo (The Cannon Was Red Hot, 2014) was nominated for the “Dablin Impact” Prize, which is awarded in this town for the best novel published in the English language.

He lives and works in Belgrade, where he is the owner and editor of the publishing house VIA. He is a columnist for the daily Politika, and occasionally writes for several media houses in our country and abroad. He is a member of the group P 70 and the Serbian Literary Society.

The Cannon Was Red Hot by Vladimir Kecmanović is undoubtedly the bravest Serbian novel of the 21st century.

Slobodan Vladušić

The Cannon Was Red Hot is the most difficult poetic hit of Serbian literature on behalf of the unspeakable sufferings during the 1990s.

Aleksandar Jerkov

Kecmanović is, in his potentiality, a truly great author, one of those that Serbian literature of the early 21st century could be remembered by. Moreover, something quite subjective: everything in me struggles against this book, because everything I have written about Sarajevo siege is against it, but I cannot refute its greatness.

Miljenko Jergović

At the beginning of the last century there was Crnjanski, with his unrepeatable endless sentences, which, cut by countless commas, washed over their readers like a sea. At the beginning of this century that follows, there is Vladimir Kecmanović, with short, pointed sentences that drive into our foreheads like nails. We have come full circle.

Bojan Bosiljčić

The new novel by Vlada Kecmanoć is a work that can be put into the genre of “open veins.” It is written in the language of his childhood, in the dialect with omitted vowels where the meanings of words are lost in an avalanche of passion and feelings that take the author’s heroes through powerful stories. Everything done on this book was set on a genuine base, but the lively characters and their destinies intertwine following a formula of the history of the last Yugoslav war. A brilliant example! The Serbian writer transcends in the language of Bosnian Muslims; courageous respect for the neighbour and melancholic knowledge of Kasbah and its laws; finding the formula for the tragedy of the book’s hero, Murat, and later his son who identifies himself with Osama Bin Laden. The novel Osama – yet another triumph of Kecmanović’ altruism.

Emir Kusturica

Kecmanović’ truth prefers to be spoken through the mouths of children or Fools for Christ. This story is also told in a humorous and invincible street language. Moreover, a sadder story has rarely been told in a more humorous language.

Vladimir Pištalo

If language is really, as a witticism has it, a “dialect with an army and a navy,” then in a higher sense, a dialect gains dignity when a great work of art is told in it… Kecmanović masterfully fits his literary world into the tradition of Andrić, and perhaps the greatest similarity between Kecmanović and Andrić lies in his deep understanding of tragedy inherent in the historical destinies of Bosnian Muslims, even the compassion for this tragedy.

Muharem Bazdulj